The Dead Hand

22 September 2009 | C-bomb, Doomsday Machine, Doomsday Men, Dr Strangelove, Hiroshima, nuclear weapons | 4 comments

On 13 November 1984, a Soviet missile was launched from Kapustin Yar, east of Stalingrad. About forty minutes later an R-36M intercontinental ballistic missile blasted off from an underground silo in Kazakhstan. Known to Western intelligence experts as the SS-18 Satan missile, it was capable of carrying either a single 24-megaton warhead or eight independently targeted 600-kiloton warheads. The bomb that killed some 200,000 people at Hiroshima was just 12 kilotons.

The launch was monitored by the West’s spy satellites. But it was an unexceptional moment in the history of the arms race and soon forgotten. Only after the Berlin Wall had been breached, and the ice of the cold war began to thaw, did military analysts realize the significance of these otherwise unexceptional rocket launches. They were the first operational test of what the Western press later described as ‘Russia’s doomsday machine’.

In my book Doomsday Men, I showed how popular culture played a vital role in inspiring the dream of the superweapon, a dream that in the nuclear age turned into the nightmare of mutually assured destruction, or MAD.

More than any other weapon, it was Leo Szilard’s chilling notion of the cobalt bomb (first described on American radio in 1950) that came to symbolize the threat of global nuclear destruction. The C-bomb consisted of one or more massive hydrogen bombs jacketed with cobalt. It was the ultimate weapon, a doomsday device which could spread radioactive fallout across the entire planet.

More than any other weapon, it was Leo Szilard’s chilling notion of the cobalt bomb (first described on American radio in 1950) that came to symbolize the threat of global nuclear destruction. The C-bomb consisted of one or more massive hydrogen bombs jacketed with cobalt. It was the ultimate weapon, a doomsday device which could spread radioactive fallout across the entire planet.

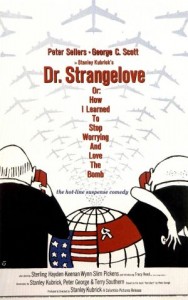

As throughout the history of superweapons, fiction and film played a key role in exploring the horrific implications of the C-bomb and how it could be used to create a doomsday machine, most famously in Peter George’s best-selling thriller Red Alert (1958) and Stanley Kubrick’s cold-war classic (based on George’s novel) Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964).

As Ambassador DeSadeski explains in Dr Strangelove: ‘If you take, say, fifty H-bombs in the hundred megaton range and jacket them with cobalt thorium G, when they are exploded they will produce a doomsday shroud. A lethal cloud of radioactivity which will encircle the earth for ninety-three years!’

As Ambassador DeSadeski explains in Dr Strangelove: ‘If you take, say, fifty H-bombs in the hundred megaton range and jacket them with cobalt thorium G, when they are exploded they will produce a doomsday shroud. A lethal cloud of radioactivity which will encircle the earth for ninety-three years!’

Twenty years after Kubrick’s film depicted the world being destroyed by a Soviet doomsday machine, the real one became operational. Nicknamed by its commanders ‘The Dead Hand’, it was a sophisticated system of sensors, communication networks and command bunkers, reinforced to withstand nuclear strikes. At its heart was a computer. As soon as the Soviet leadership detected possible incoming missiles, it activated the system, known by its code name ‘Perimetr’. Part of the secret codes needed to launch a Soviet nuclear strike were released and the computerized process set in motion. Then, like a spider at the centre of its web, the computer would watch and wait for evidence of an attack.

As I said in my book, the way it worked was strikingly similar to the doomsday machine described by Dr Strangelove. He explained that the computer was ‘linked to a vast interlocking network of data-input sensors which are stationed throughout the country and orbited in satellites. These sensors monitor heat, ground shock, sound, atmospheric pressure and radioactivity.’

Much about the Dead Hand system is still shrouded in secrecy. Russian arms expert Bruce Blair revealed the first details in 1993. Recently declassified interviews with former Soviet officials have cast fresh light on the system. They show that there were doubts about its reliability. Some even questioned whether it was ever fully deployed. However, these interviews also reveal the shocking possibility that the Dead Hand system may have been fully automatic.

Previously it was thought that once the computer detected signs of an attack, it required human approval before any counter attack could be launched. A Soviet officer buried deep underground in a command post would have had the unenviable task of authorising the Dead Hand to complete its lethal task. But these interviews raise the possibility that the Dead Hand had eliminated the need for any human control. It may be that the Dead Hand could launch the entire Soviet nuclear arsenal as soon as its sensors indicated that an attack had occurred. That idea is truly terrifying.

A machine would be responsible for unleashing nuclear weapons with a total destructive power as much as 50,000 times greater than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Even without Szilard's C-bomb, who knows what would be left alive after such a nuclear holocaust.

Intriguingly, Nicholas Thompson, writing in Wired today, argues that Perimetr was actually designed ‘to keep an overeager Soviet military or civilian leader from launching prematurely during a crisis’. In other words, it was an insurance policy meant to reassure the Kremlin’s hawks that their country could hit back, even after a sneak attack by submarine launched missiles, which would have given the Soviet leadership barely thirteen minutes advance warning of a devastating attack.

As far as anyone knows, the Dead Hand remains operational. What is truly worrying, even today, is the secrecy that continues to surround the whole subject. Thompson has found that neither George Schultz nor former CIA director James Woolsey had heard of the Dead Hand system. Former Soviet era officials will still not discuss it. One who dared to talk died in mysterious circumstances. Such secrecy is, as Dr Strangelove realised, disastrous: ‘Yes, but the...whole point of the doomsday machine...is lost...if you keep it a secret! Why didn’t you tell the world, eh?’

The doomsday machine is supposed to be the ultimate deterrent. But if no one knows that the deterrent exists... Well, you've all seen the final scenes of Dr Strangelove.

The Aptly-Named “Dead Hand” » Jeremy Hatch | 08 December 2009

[...] Dr. Strangelove? The Doomsday Machine? It turns out that something very like it, called the Dead Hand, was actually operational, in the USS... at latest, and its pieces may still be around [...]

Thomas | 09 April 2010

Doomsday-by-cold-war seems to get substituted by doomsday-by-climate-collapse, making me wonder is, aside weird strategic forecasts as in the review quoted below, weird practical concepts become implemented, as during cold war:

"WHEN a climate scientist forecasts that global warming will trigger mega-famines, floods of refugees and geopolitical meltdown, we may fear that they have a myopic world view. When a security specialist says the same thing, we should start to wonder. ... It makes for a good read, but do I believe it? Not at all. Dyer's view of both humanity and climate is too mechanistic and his view of politics too

militaristic. The world is far stranger, and the future will be far odder, than anything imagined in a war studies seminar based on the predictions of climate modellers. We know less than we think. But as an insight into what the military strategists imagine is going to happen as a result of climate change, this book is truly terrifying."

PD Smith | 09 April 2010

Thanks for that Thomas - sounds like an interesting book, one I should read...

The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy (2009) | 03 January 2014

[...] of the Soviet military-industrial complex is especially disturbing. The book’s title comes from a computer network, “a real-world doomsday machine,” built in the 1980s to retaliate in the event the Soviet [...]